Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

| Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| 26°41′40″N 127°52′41″E / 26.69439°N 127.87794°E | |

| Date opened | 1 November 2002 [1] |

| Location | Motobu, Okinawa, Japan |

| Land area | 19,000 m2 (200,000 sq ft)[1] |

| No. of animals | 11,000[2] |

| No. of species | 720[2] |

| Volume of largest tank | 7,500,000 litres (1,981,000 US gal)[4] |

| Total volume of tanks | 10,000,000 litres (2,642,000 US gal)[5] |

| Annual visitors | 3.5 million + [3][1] |

| Memberships | JAZA[6] |

| Major exhibits | The Kuroshio Sea tank etc. |

| Management | Okinawa Churashima Foundation |

| Website | churaumi |

The Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium (沖縄美ら海水族館, Okinawa Churaumi Suizokukan), formerly known as the Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium, is a public aquarium located within the Ocean Expo Park in Okinawa, Japan. The aquarium's Kuroshio sea tank was the largest aquarium tank in the world until it was surpassed by the Georgia Aquarium in 2005.

The aquarium has the exhibit, "Encounter the Okinawan Sea",[7] which reproduces the sea of Okinawa and most of the creatures that live in it.[2] Churaumi was selected as the name of the aquarium by public vote amongst Japanese people: chura means "beautiful" or "graceful" in the Okinawan language, and umi means "ocean" in Japanese.

It is a member of the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums (JAZA),[6] the aquarium is accredited as a Registered Museum by the Museum Act from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.[8]

History

[edit]Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium

[edit]

Expo '75 was held in Okinawa, Japan, at the Ocean Expo Park, where an aquarium centered on marine life was displayed. In 1976, the Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium was established as a national park on the site of the venue.[9] The former aquarium was designed by Fumihiko Maki. [10]

The Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium and the Okichan Theater started operations with the facilities used at the Expo. At that time, the largest main tank in the aquarium had a water volume of 1,100,000 litres (291,000 US gal), which was the largest in the world.[11][12]

The Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium is one of the first public aquariums in the world that breeds large sharks and rays such as whale sharks and manta rays.[11][12]

The captivity of manta ray dates back to at least 1978.[13] The first individual was captured by fishermen, entangled in a net, and threaded through a rope into a spiracle, which severely damaged it. Despite its injuries, the aquarium managed to transport it alive to a tank, where it recognized the tank walls, swam to avoid them, and ultimately survived for 4 days.[14][15] The second manta ray was brought in in 1985, but died on the same day. The third manta ray brought in was the first to be successfully kept for a long period of time, and the third manta ray went until from 1988 to 2000.[13] The longest kept manta ray was a record that the male reef manta ray, which lived in captivity in 1992, lived for about 23 years.[16]

The first attempt of keeping whale sharks in an aquarium was in 1980.[9][17] Most were obtained from incidental catches in coastal nets set by fishers (none after 2009), but two were strandings. Several of these were already weak from capture or stranding and some were released,[17] but initial survival rates were low.[18] After the initial difficulties in maintaining the species had been resolved, some have survived long-term in captivity. The record for a whale shark in captivity is an individual that, as of 2024, has lived for more than 29 years in the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium from Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium.[19]

At a symposium held in Baltimore in 1985, the Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium was rated to have the most advanced breeding technology in the world for long-term rearing.[11] In 1988, the aquarium won the first Koga Award from JAZA in Japan for breeding two generations of whitetip reef sharks.[20]

From the collapse of the bubble economy, as the park lost incoming tourists, it was believed that a new aquarium would help revive the area and celebrate Okinawa's marine tradition. In addition, since the facility was built for a short-term expo, it deteriorated significantly, and a plan to build a new aquarium was proposed.[5]

Opening of Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium

[edit]

The Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium was closed in August 2002 due to facility deterioration, and the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium was opened on 1 November 2002, with a new facility designed by Yukifusa Kokuba(1939–2016) is an architect from Okinawa.

The number of visitors in the year before the old aquarium closed was about 430,000, but the number of visitors in the year after the opening of the new building increased to 2.75 million.[22] The number of visitors has continued to increase, with the number of visitors reaching 3,784,132 in 2017 and the cumulative number of visitors reaching 50 million in 2019.[3]

The aquarium's facilities also included a dolphin studio and a sea nursery, but due to deterioration of the concrete and other factors, they have been out of use since the end of January 2007 and have all been removed.[9]

Since 2007, Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium has been conducting an annual learning program for elementary schools in Motobu-cho and Nago city, "Environmental Learning from Sea Turtles," which is an educational activity about ecology and the natural environment through the breeding of sea turtles.[23]

In 2012, a general rest area (Churaumi Plaza) opened.[9] Since 2018, the aquarium has opened its offshore research facility to the public by OKINAWA SAKANA CAMPANY.[24]

In 2020, the number of tourists in Okinawa Prefecture decreased significantly due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[25] The aquarium supervised the Sony aquarium, which was held at the Ginza Sony Building every summer until 2019 before the COVID-19 disaster. The fish once displayed at the Sony Aquarium were brought in from the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium.[26][27]

In 2023, he was awarded the Koga Award, the highest prize in Japan for rare species breeding, for his research activities in sea turtle breeding on the IUCN Red List and Appendix I of CITES, for his ecological and conservation research through captive breeding of sea turtles and breeding over two generations.[28]

The Okinawa Churashima Foundation has been certified under the "Okinawa Prefecture CO2 Absorption Certification System" for the management of a total of 380 Garcinia subelliptica, Dypsis lutescens, and other trees around the aquarium during the 2023 CO2 absorption certification period.[29]

Aquarium

[edit]

The public aquarium is a part of the Ocean Expo Park located in Motobu, Okinawa. The aquarium is made up of four floors, with tanks containing deep sea creatures, sharks, coral, and tropical fish. The aquarium is set on 19,000 m2 (200,000 sq ft) of land, with a total of 77 tanks containing 10,000 m3 (2,600,000 US gal) of water. Water for the saltwater exhibits is pumped into the aquarium from a source 350 m (1,150 ft) offshore, 24 hours a day.[31][32]

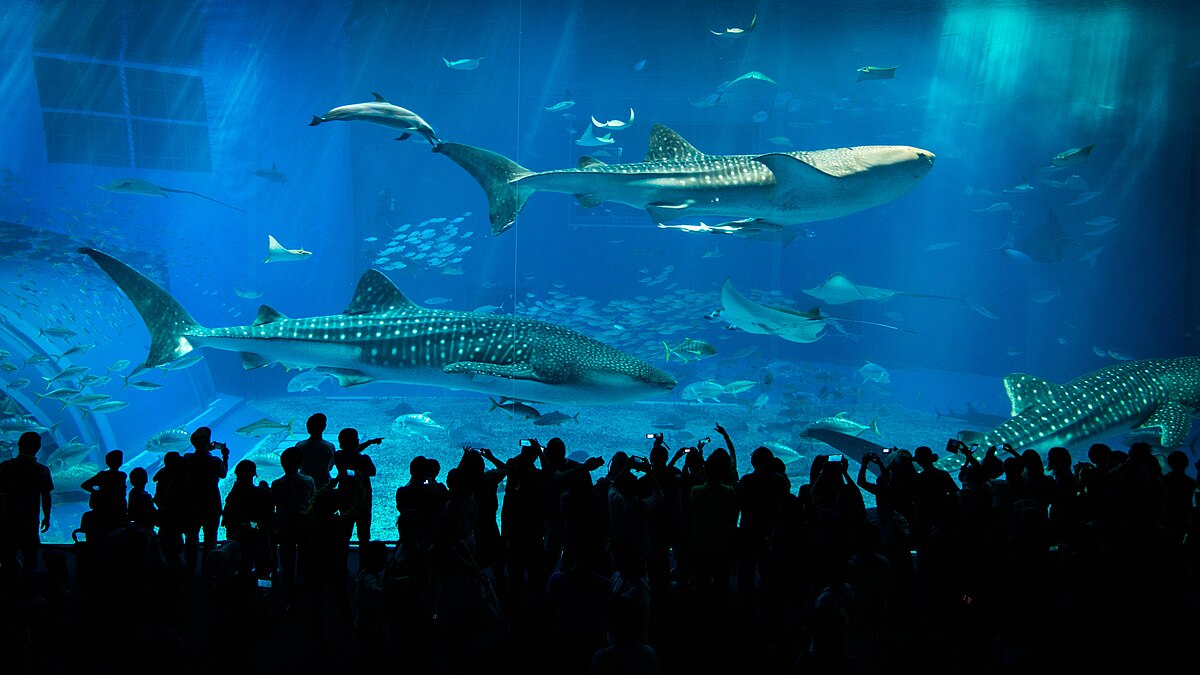

The Kuroshio Sea

[edit]The main tank, called the Kuroshio Sea, is 35 metres (115 ft) long, 27 metres (89 ft) wide and 10 metres (33 ft) deep.[33] It holds 7,500,000 litres (1,981,000 US gal) of water and features an acrylic glass panel measuring 8.2 by 22.5 metres (27 by 74 ft) with a thickness of 60 centimetres (2 ft),[34] the largest such panel in the world when the aquarium was opened.[4][35]

Whale sharks and manta rays are kept alongside many other fish species in the main tank.[4] Four species of mobula are kept at the aquarium, including the manta ray.[36]

Since 2015, the aquarium has also had a reef manta ray with a all black body.[37] Since 2018 they also keep giant oceanic manta ray.[38] This species and the reef manta ray were only recognized as separate species in 2009; they were both classified as Manta birostris until then.[39][40][41] The world's first birth of a manta ray in captivity was at the aquarium in 2007. By the time the mother died in 2013, seven puppies were born and four survived.[42][43][44][45] The disc width of the largest pup born at aquarium was about 1.92 m (6 ft 4 in). [46] In August 2024, a female all black body manta ray kept in the Kuroshio tank gave birth. This is the first time in 11 years that a manta ray has birth, and the first case of all black body manta ray birth in the world. The pups were born black all over like their mother, 1.6 metres (5 ft) wide, and weighed 42 kilograms (93 lb).[47]

Okinawa Churaumi is trying to breed whale sharks in captivity, which has never been achieved by an aquarium. Their oldest male reached sexual maturity around 2012 and began to show an interest in females in 2014. The exhibited until 2021 female was on display[48] (another is maintained away from the public) is 8 m (26 ft) long.[49] There were three whale sharks, but they have been moved to a separate tank to make room for breeding.[50] In 2021, a 13-year-old female whale shark that had been in captivity in the Kuroshio Sea tank was transferred to a medical treatment tank in the sea due to poor health, and later died. The cause of death is thought to be feeding difficulties from skeletal abnormalities in the jaw and a twisted pylorus.[51][48]

The Coral Sea

[edit]

In the Coral Sea tank, 450 colonies of reef-building corals of about 80 species are bred and exhibited.[52] The tank has a capacity of 300,000 litres (79,000 US gal), no roof, a structure that allows strong sunlight to enter, and a constant supply of fresh seawater to enable large-scale breeding of coral.

The Coral Sea tank is made to emulate the coral reefs in Motobu.[52] The aquarium has confirmed simultaneous coral spawning for 22 consecutive years.[53] In 2021, the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium was temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was confirmed that Acropora microphthalma gave spawned in the daytime for the first time.[54]

In the same zone as the Coral Sea tank is another tank called The Sea of Tropical fish tank. This tank has a capacity of 700,000 litres (185,000 US gal) liters of water and In addition to coral houses 180 species of fish, including large fish that are difficult to breed in the Coral Sea tank, which specializes in coral propagation.[55] In this tank, the shallow rocky areas to the depths of the caves in the coral reefs of Okinawa are reproduced in a single tank.[55]

In 2024, the tropical fish tank was the first in the world to exhibit Pinjalo lewisi, a fish that had never been kept in captivity, alive.[56]

The Shark Research Lab

[edit]Sharks such as bull sharks, tiger sharks, silvertip sharks, and silky sharks are bred in the shark research lab tank. Some bull sharks kept in aquariums have lived for more than 45 years as of 2024.[19] The lab also displays many skeletal and fetal specimens of sharks.[57]

In 2016, the aquarium showed an attempt to raise an adult great white shark. The great white shark exhibit was successful, but it died three days later, leading to criticism from animal rights groups.[58] In 2019, aquariums captured a pregnant tiger shark and succeeded in giving birth in a shark research lab tank.[59]

The Deep Sea

[edit]

Most of the deep-sea organisms at the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium were collected from depths greater than 300 m (980 ft) around Okinawa. Because many deep-sea species are undiscovered, rare species, including new species and species recorded for the first time, are often exhibited, and the actual deep-sea environment observed by the ROV is reproduced.[60][61]

In 2017, ROV surveys were conducted in the waters near Okinawa at a depth of around 200 m (660 ft). A total of 20 species of deep-sea invertebrates were collected and nine species, including Holothuria dura, were displayed.[62]

In the same year, also discovered areas with high densities of Lyrocteis imperatoris and Saracrinus nobilis, which are considered difficult to capture and keep in captivity. Especially for Lyrocteis imperatoris, succeeded in keeping them for more than one year, and bred individuals were kept and The breeding individuals were also exhibited.[62]

The aquarium has succeeded for the first time in captive breeding of salamander sharks, which live at depths of around 600 m (2,000 ft) in the seas around Japan. They are oviparous, and the eggs were echogenically examined regularly for 18 months until they hatched.[63] The aquarium also saw sharks give birth in 2014 and 2017.[64]

Okichan Theater and Dolphin Lagoon

[edit]

Near the aquarium is the Dolphin Show Stadium, called the Okichan Theater, where viewers can touch the animals and watch the show's performance for free.[65] There is also a dolphin contact facility called Dolphin Lagoon, which houses several species of dolphin.[66][67] The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin named Okichan has been owned since the opening of the Okinawa Ocean Expo Aquarium and has been bred for 48 years as of 2024.[19]

In 2003, the bottlenose dolphin named Fuji's caudal fin was 75% necrotic and had to be resected. The aquarium collaborated with Bridgestone to develop the world's first artificial caudal fin to attach to Fuji.[68][69][70] Fuji died of infectious hepatitis in 2014 at an estimated age of 45.[71]

Other facility

[edit]

There is a manatee pool and a sea turtle pool, Both are free and open to the public.[72][73] A spawning ground dedicated to sea turtles is set up in the exhibition facility.[74] [75]

Spawning are observed every year on the spawning grounds.[76] The sea turtle pool was the first in the world to successfully breed the third generation of Hawksbill sea turtles in captivity.[77] In 2022, a research paper on sexual maturity in Loggerhead sea turtles was published in the Herpetological Review, published by the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.[78]

West Indian manatees were first exhibited in 1978 when the Mexican government gave two of them to the aquarium, and two new ones were sent in 1997.[9] Manatees have given birth in the past 1990, 2001, and 2021, and a male manatee named "Yucatan" had a total of 6 times Involved in childbirth with several females until his death in 2019 at age 42.[79][80]

Research and conservation

[edit]

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Churaumi Aquarium conducts research on the diversity of marine life found around Okinawa, and is engaged in activities that contribute to the conservation and sustainable use of the natural environment.[81][original research?]

At the aquarium, the Okinawa Churashima Foundation supervises conservation activities and conducts animal research.[20][original research?] The aquarium has won the breeding award from the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums (JAZA) for 26 kinds of animals, such as the reef manta ray and Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin.[20] In particular, it is characterized by the large breeding of large sharks and rays, which are rare in other locations.[citation needed]

Shark and ray breeding and research

[edit]

Many researchers are located at the Okinawa Churashima Foundation Research Center, including Keiichi Sato (佐藤圭一), a principal researcher who specializes in shark and ray research and has authored several papers through his work at the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium.[82]

The aquarium collects blood from wild whale sharks, measures the total length and circumference of the body, collects tissues for DNA analysis and chemical analysis, and observes behavior in the natural sea using electronic labels to obtain important information on the breeding habits and ecology of whale sharks. It also conducts tests for future breeding, such as monitoring the behavior of whale sharks during breeding and the concentration of hormones in the blood obtained by blood sampling.[20]

Aiming to achieve ex situ conservation of rare sharks,[83] the aquarium's research institute began developing an artificial uterus apparatus for shark embryos in 2017. In October 2020, the aquarium began incubating two live embryos of the deep-sea slendertail lanternshark (Etmopterus molleri) in the artificial uterus. After five months, the two embryos were successfully born in a world's first.[84][85] The sharks died 4 days and 25 days post-birth respectively, likely due to failure in adapting to the post-birth seawater environment.[85] From 2021 to 2022, the aquarium further introduced 30 slendertail lanternshark embryos into the artificial uterus, of which 6 were ultimately successfully born.[86] One shark incubated for roughly a year and born in April 2023 continued to grow stably after birth and later turned one year old.[13][87] The shark has been exhibited in the aquarium since 25 April 2024.[87]

Humpback whale research

[edit]The aquarium conducts surveys of humpback whales to study their ecology and conditions. Humpback whales are known to seasonally migrate, feeding in the cold waters near Russia and Alaska during the summer, and breeding and raising their young in the warmer waters near Hawaii, Mexico, and Okinawa during the winter. As of 2023, the aquarium been involved in such research for more than 30 years, and has identified approximately 1,900 humpback whales near the Kerama Islands and the Motobu Peninsula via the unique patterns on the whales' tail flukes.[88]

In a 2021 joint study with the National Museum of the Philippines, it was revealed that 43.48% of humpback whales around the Philippines were the same individuals confirmed in Okinawa and were moving between the two waters, revealing the migration route of humpback whales between Okinawa and the Philippines from the previously unknown Russia feeding ground.[clarification needed][89]

A paper on the diurnal variation of humpback whale sounds in Okinawa was published in the journal Marine Mammal Science and received an award as one of the most cited papers in the journal in 2021–2022.[90]

Discovery of new species

[edit]In August 2010, the aquarium described Hexagonaloides bathyalis as a new genus and species of the trapeziid crab (coral crab), in collaboration with the Natural History Museum and Institute in Chiba and the Biological Sciences Department of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.[91][92] Unlike most coral crabs, which live in shallow waters within 100 m (330 ft) of depth, the species lived in the deep sea at depths below 247 m (810 ft). In January 2019, the aquarium began exhibiting an individual of the species for the first time in the world.[92]

In February 2019, the aquarium described Eumunida balteipes as a new deep-sea species of the squat lobster, in collaboration with the Estuary Research Center of Shimane University.[93][94][95] The name "balteipes" refer to the stripes on the species' legs, which is a key feature of the species. The aquarium had exhibited individuals of the species for over 10 years by then, but they were believed to be part of the Eumunida pacifica species instead.[94] The species is extremely rare and its sighting has not been reported outside of Okinawa's Kume Island as of 2021. The aquarium successfully bred the species for the first time in the world in December 2021.[95]

In December 2019, the aquarium described Synactinernus churaumi as a new species of the sea anemone, in collaboration with the University of Tokyo, the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo, the International Center for Island Studies at Kagoshima University, and the Natural History Museum and Institute in Chiba.[96] The scientific paper, published in the Japanese journal Zoological Science, was awarded the 2020 Zoological Science Award.[97] The species is the second species in the Synactinernus genus, which was first described in 1918 with the discovery of Synactinernus flavus.[98]

In December 2019, the aquarium described Olindias deigo as a new species of the flower hat jelly.[99] It was the first time in 114 years that a new species was recorded in the Olindias genus. The species' appearance is similar to the flower hat jelly, but differs in the number of outer umbrella tentacles, and is paler in colour. The name "deigo" comes from a common Okinawan flower. From January to February 2020, the aquarium exhibited two individuals of the species for the first time in the world.[100]

In January 2020, the aquarium described Plectranthias ryukyuensis as a new species of deep-sea anthias, in collaboration with Kagoshima University.[101] The species is found only in the waters around the Amami Islands and the Okinawa Main Island, and is thought to be endemic to the Ryukyu Islands. As of 2020, only seven individuals of the species have been found, two of which were displayed by the aquarium starting February 2020 for the first time in the world.[102]

In January 2024, the aquarium described Churaumiastra hoshi as a new genus and species of starfish, in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution, the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency, and the National Museum of Nature and Science.[103] This description was done based on a specimen collected by the aquarium using a remotely operated vehicle in March 2021. The species is extremely rare and lives at depths of 100–250 m (330–820 ft) in the Philippines, Australia, and Okinawa. The aquarium began exhibiting the species for the first time in the world in January 2024.[104]

Gallery

[edit]Exterior

Aquarium

Main tank aquarium

Okichan Theater

Sea turtle and manatees

See also

[edit]- Tropical & Subtropical Arboretum (Facilities in Ocean Expo Park)

- Expo '75

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Comparison of major aquariums in the Greater Tokyo Area (Japanese)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c "よくある質問 どのくらいの数の生き物を飼っていますか?". 沖縄美ら海水族館. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b 国営沖縄記念公園事務所-利用者状況 内閣府沖縄総合事務局 2021-05-07

- ^ a b c "Amazing Engineering: the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium". wayfaring.info. Wayfaring Travel Guide. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ a b "施設概要 沖縄美ら海水族館". 沖縄美ら海水族館. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b JAZA. "正会員名簿【水族館】" (in Japanese). Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "About Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium - Okinawa Travel Guide | Planetyze". Planetyze. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ "法律上の位置付けがある登録博物館・指定施設". 文化庁. 27 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e 海洋博公園の歴史

- ^ 宮沢浩. イラストで読む建築 日本の水族館53次. 青幻舎.

- ^ a b c 内田詮三 (2012). 沖縄美ら海水族館が日本一になった理由. 光文社新書.

- ^ a b 国営沖縄記念公園水族館 (1988). 水族館動物図鑑. 新星図書出版株式会社.

- ^ a b c d 佐藤, 圭一 (15 June 2022). 沖縄美ら海水族館はなぜ役に立たない研究をするのか? (in Japanese). 産業編集センター. ISBN 978-4863113350.

- ^ 板鰓類研究会報 第 14 号 (PDF). 板鰓類研究会.

- ^ 板鰓類研究会報 第 46 号 (PDF). 板鰓類研究会.

- ^ "平成26年度 沖縄美ら海水族館年報" (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ a b Rui Matsumoto; Minoru Toda; Yosuke Matsumoto; Keiichi Ueda; Miyuki Nakazato; Keiichi Sato; Senzo Uchida (2017). "Notes on Husbandry of Whale Sharks, Rhincodon typus, in Aquaria". In Mark Smith; Doug Warmolts; Dennis Thoney; Robert Hueter; Michael Murray; Juan Ezcurra (eds.). Elasmobranch Husbandry Manual II. Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 15–22. ISBN 978-0-86727-166-9.

- ^ Goodman, Brenda (14 June 2007). "Georgia Aquarium Mourns Another of Its Whale Sharks". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ a b c 令和五年度 沖縄美ら海水族館 年報 (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Breeding in Captivity". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "海人門(ウミンチュゲート) 沖縄美ら海水族館". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ 1.沖縄ブロックの現状と課題 2021-05-07

- ^ "「ウミガメから学ぶ環境学習」小学生による学習成果の発表会を実施". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "2018年1月の新規掲載情報". やんばる旅ナビ.

- ^ "沖縄美ら海水族館、開業以来初のマイナス収支 県に移管した7施設 4264万円の赤字". 沖縄タイムス. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "「46th Sony Aquarium」開催 美ら海からやってきた色鮮やかなお魚を、今年も銀座でお披露目 2013年7月19日(金)初日オープニングイベントレポート". MSN産経ニュース. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "銀座 ソニービル 「Sony Aquarium 2006」". ソニー企業株式会社. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ "水族館のウミガメ繁殖研究活動が希少種繁殖の国内最高賞「古賀賞」受賞しました。".

- ^ "「沖縄県CO2吸収量認証制度」の認証を受けました". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "黒潮探検(水上観覧コース)". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ 建築思潮研究所 (2008). 水族館. 建築資料研究社.

- ^ "Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium". oki-churaumi.jp. Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium | the Kuroshio Sea". Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Welcome to Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium". oki-churaumi.jp. Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ The size of this panel was surpassed in 2008 when a larger panel was installed in the Dubai Mall Aquarium

- ^ "帰って来た「イトマキエイ」!世界唯一ヒメイトマキエイとの同居展示".

- ^ "日本初!『ブラックマンタ』展示開始!". 21 December 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "The world's largest ray! The giant manta!". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 4 January 2019. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "3 Years in a row! This year too, a baby Manta was born in the Oki". oki-churaumi.jp. Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Marshall, A. D.; Compagno, L. J. V.; Bennett, M. B. (2009). "Redescription of the genus Manta with resurrection of Manta alfredi (Krefft, 1868) (Chondrichthyes; Myliobatoidei; Mobulidae)". Zootaxa. 2301: 1–28. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2301.1.1. ISSN 1175-5326. S2CID 81789023.

- ^ Ryo Nozu; Kiyomi Murakumo; Rui Matsumoto; Yosuke Matsumoto; Nagisa Yano; Masaru Nakamura; Makio Yanagisawa; Keiichi Ueda; Keiichi Sato (2017). "High-resolution monitoring from birth to sexual maturity of a male reef manta ray, Mobula alfredi, held in captivity for 7 years: changes in external morphology, behavior, and steroid hormones levels". BMC Zoology. 2 (14). doi:10.1186/s40850-017-0023-0.

- ^ "We have just recently had our 4th successful manta ray (Manta birostris) birth in captivity at Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium". oki-churaumi.jp. Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ "平成22-23年度 沖縄美ら海水族館年報" (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ "平成24年度 沖縄美ら海水族館年報" (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ "平成25年度 沖縄美ら海水族館年報" (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ^ "Manta Ray Manta birostris (Donndorff, 1798) in Captivity". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "【世界初!!ブラックマンタが産まれました!】". Okinawa Churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ a b "美ら海水族館のジンベエザメ死ぬ 沖縄タイムス".

- ^ "Breeding in Captivity". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "水族館の新しいこころみ!ジンベエザメの繁殖に向けた飼育展示について".

- ^ "Whale sharks in the Kuroshio Sea tank".

- ^ a b c "The Coral Sea". Okinawa churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "22年連続!水槽内にも初夏の訪れ 5月29日「サンゴの一斉産卵」確認". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "【動画あり】展示用サンゴで国内初 昼の産卵に美ら海水族館が成功 ピンクの粒が幻想的に舞い上がる". Okinawa times. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ a b "熱帯魚の海". Okinawa churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "幻の赤いシチューマチ「セダカタカサゴ」を世界初展示‼". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "サメ博士の部屋". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "Great white shark dies after three days in captivity in Japan". The Guardian. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "World's first! Tiger shark born in the aquarium.Exhibited now at the Shark Research Lab tank". 1 July 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "深層の海". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "深海の小さな生き物". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ a b "平成29年度 沖縄美ら海水族館年報" (PDF). Okinawa Churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "【すご技生物~深海編~⑤卵 イモリザメ♪後編】". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "水族館生まれ!2歳のノコギリザメ展示開始". 沖縄美ら海水族館.

- ^ "Dolphin Show (Okichan Theater)". Okinawa churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "オキちゃん劇場/イルカショー". Okinawa churaumi aquarium. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "Pygmy killer whale". Churaumi Official Fish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "A new beginning for Fuji the dolphin". 15 September 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Fuji, the Bionic Dolphin With the Artificial Fin (video)". 26 December 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Fuji The Dolphin's Rubber Tail". CBS News. 14 December 2004. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Aged dolphin with artificial tail fin dies at Okinawa aquarium". Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "マナティー館". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Sea Turtle Pool". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "The only place in the world exhibiting four different species of baby sea turtles!". Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Dolphin Feeding Program / Turtle Feeding Program / Manatee Feeding Program". Okinawa churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "【ウミガメ産卵調査奮闘記】". 美ら海だより.

- ^ "世界初 タイマイの3世代目の繁殖成功!". 沖縄美ら島財団.

- ^ "アカウミガメ 性成熟がはじまる年齢が明らかに!". Okinawa churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "【FILMS】沖縄海洋博 マナティ". 沖縄アーカイブ研究所. 29 October 2020.

- ^ "新しく仲間入り!オスのマナティーが誕生しました‼". Okinawa churaumi aquarium.

- ^ "Research publication and activity". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ 第5回 海に憧れた少年がサメ博士になるまでとこれから. National Geographic (in Japanese).

- ^ "Latest news about the artificial uterus apparatus for sharks! Successful stable rearing of shark pups born from an artificial uterus". Okinawa Churashima Foundation.

- ^ Nagamine, Kotaro (19 March 2022). "World's first shark embryo incubated in artificial uterine fluid until birth is on display at Churaumi Aquarium". Ryūkyū Shimpō. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b Tomita, Taketeru; Toda, Minoru; Murakumo, Kiyomi; Kaneko, Atsushi; Yano, Nagisa; Nakamura, Masaru; Sato, Keiichi (2 March 2022). "Five-Month Incubation of Viviparous Deep-Water Shark Embryos in Artificial Uterine Fluid". Frontiers in Marine Science. 9. doi:10.3389/fmars.2022.825354. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Tomita, Taketeru; Toda, Minoru; Kaneko, Atsushi; Murakumo, Kiyomi; Miyamoto, Kei; Sato, Keiichi (27 September 2023). El Basuini, Mohammed Fouad (ed.). "Successful delivery of viviparous lantern shark from an artificial uterus and the self-production of lantern shark luciferin". PLOS ONE. 18 (9): e0291224. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1891224T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0291224. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 10530027. PMID 37756258.

- ^ a b "A world's first! The exhibition of a one-year-old Mollers lantern shark that was born using the artificial uterus apparatus". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 25 April 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ "Surveys of the humpback whale Research on marine organisms". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Acebes, Jo Marie; Okabe, Haruna; Kobayashi, Nozomi; Nakagun, Shotaro; Higashi, Naoto; Uchida, Senzo (8 April 2021). "Interchange and movements of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) between western North Pacific winter breeding grounds in northern Luzon, Philippines and Okinawa, Japan". J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 22 (1): 39–53. doi:10.47536/jcrm.v22i1.201. ISSN 2312-2706.

- ^ 学術誌Marine Mammal Scienceに掲載された論文が2021-2022年 同誌で最も引用された論文の1編として表彰されました!. Okinawa Churashima Foundation (in Japanese).

- ^ Komai, Tomoyuki; Higashiji, Takuo; Castro, Peter (31 December 2010). "A new genus and new species of deep-water trapeziid crab (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Trapezioidea) from the Ryukyu Islands, Japan". Zootaxa. 2555: 62–68. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.196907.

- ^ a b "World's first successful exhibition of the deep-sea crab Hexagonaloides bathyalis!". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 21 January 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Osawa, Masayuki; Higashiji, Takuo (14 February 2019). "Two large squat lobsters of the superfamily Chirostyloidea (Crustacea: Decapoda: Anomura) from the Ryukyu Islands, southwestern Japan, with description of a new species of the genus Eumunida Smith, 1883". Zootaxa. 4555 (3): 319–330. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4555.3.2. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 30790919.

- ^ a b "The discovery of a new species! The world's first exhibit of Eumunida balteipes". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 20 February 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ a b "A new species of squat lobster! Successful breeding! Parents and offspring on exhibit". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 7 December 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Izumi, Takato; Fujii, Takuma; Yanagi, Kensuke; Higashiji, Takuo; Fujita, Toshihiko (9 December 2019). "Redescription of Synactinernus flavus for the First Time after a Century and Description of Synactinernus churaumi sp. nov. (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria)". Zoological Science. 36 (6): 528–538. doi:10.2108/zs190040. ISSN 0289-0003. PMID 31833324.

- ^ "Zoological Science Award for scientific paper describing the new species Churaumi actinernid sea anemone". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 11 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ "Discovery of a new species! The world's first exhibit of the Churaumi actinernid sea anemone". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Toshino, Sho; Tanimoto, Miyako; Minemizu, Ryo (31 December 2019). "Olindias deigo sp. nov., a new species (Hydrozoa, Trachylinae, Limnomedusae) from the Ryukyu Archipelago, southern Japan". ZooKeys (900): 1–21. Bibcode:2019ZooK..900....1T. doi:10.3897/zookeys.900.38850. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 6946721. PMID 31920422.

- ^ "Discovery of a new species! The world's first display of a new flower hat jelly Olindias deigo". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Wada, Hidetoshi; Suzuki, Toshiyuki; Senou, Hiroshi; Motomura, Hiroyuki (January 2020). "Plectranthias ryukyuensis, a new species of perchlet from the Ryukyu Islands, Japan, with a key to the Japanese species of Plectranthias (Serranidae: Anthiadinae)". Ichthyological Research. 67 (2): 294–307. Bibcode:2020IchtR..67..294W. doi:10.1007/s10228-019-00725-6. ISSN 1341-8998.

- ^ "The world's first exhibition of the Churashima perchlet, a new species which is endemic to the Ryukyu Islands!". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 3 February 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Mah, Christopher L.; Kogure, Yoichi; Fujita, Toshihiko; Higashiji, Takuo (18 January 2024). "New Taxa and Occurrences of Mesophotic and Deep-sea Goniasteridae (Valvatida, Asteroidea) from Okinawa and adjacent regions". Zootaxa. 5403 (1): 1–41. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.5403.1.1. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 38480457.

- ^ "The world's first exhibition of the Churaumiastra hoshi A new species of sea star, in a new genus, discovered in Okinawan waters". Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium. 18 March 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- Official website (Japanese)

- Official website (English)

- Churaumi Official Fish Encyclopedia(Japanese)

- Churaumi Official Fish Encyclopedia(English)

- Ocean Park Homepage in English

- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium's channel on YouTube

- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium on Facebook

- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium on Twitter

- Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium on Instagram

- Bus Timetable from Asahibashi Sta. to the Aquarium

Geographic data related to Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium at OpenStreetMap